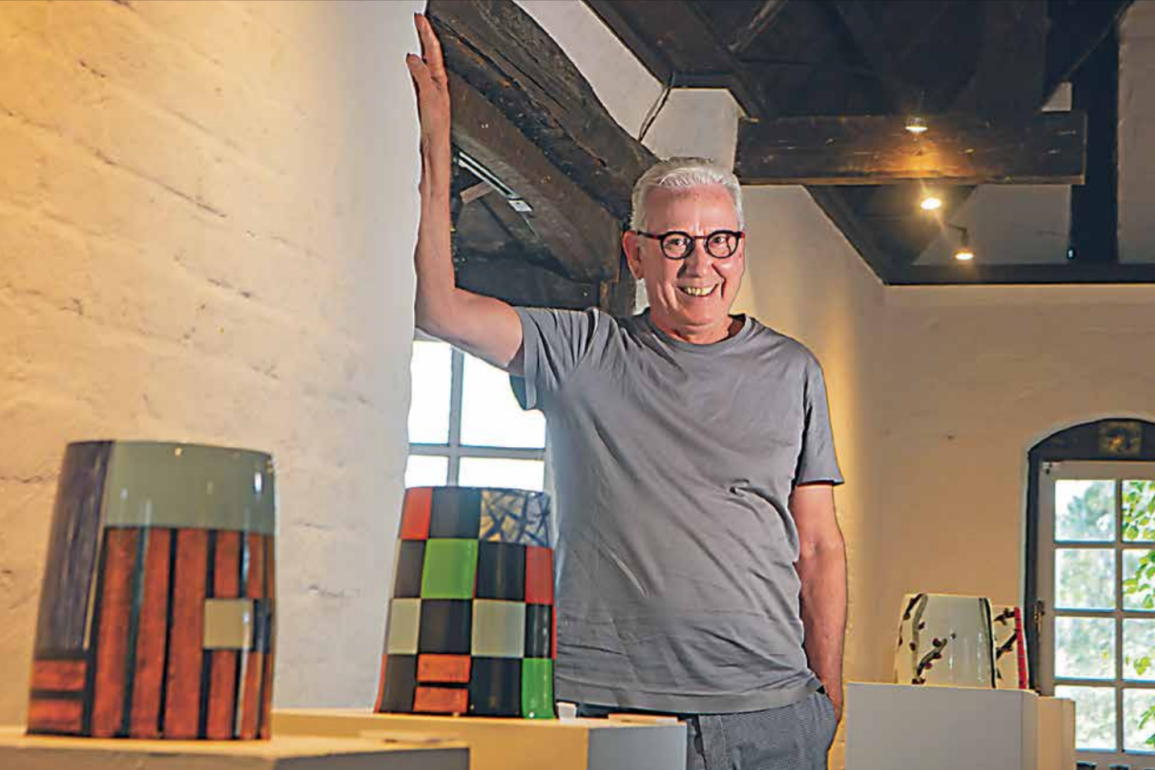

The biggest creative influence in ceramicist Kevin White’s storied career, Japanese potter Sato Satoshi, was an intense man of wisdom, but very few words. In 1982, after an 18-month scholarship, the young Englishman secured two days each week in Sato’s Kyoto studio, watching closely select techniques and behaviors he follows to this day: unfailing respect for one’s materials and appreciation of the near-sacred time spent shaping them into works of art. White, still relatively green behind the ears, was equally in thrall and terrified.

“Sato would greet me with a grunt each morning and grunt when I left in the afternoon,” says White, 69. “He was a fairly imposing character, and of course, my Japanese wasn’t much good. But then, about six months in, when I was heading home for a while, he said, ‘Hey, if you’ve got nothing to do, we’re heading out drinking later, you’re welcome to join.’ It all kind of changed after that.”

Four decades on, the vast majority spent in Melbourne, White is an internationally recognized ceramicist lauded for porcelain works that combine traditional East Asian influences with his own distinctive brushwork. He continues to exhibit the world over, is an adjunct professor at RMIT where he taught for years, and heads a pottery round at Montsalvat, a group of like-minded souls whose works help fund its Clay Talk studio. It’s his lifeblood.

“My encouraging art master at high school in Reading gave me the bug,” says White. “My father wanted me to follow him into plate making for the printing industry. Then he arranged an interview with the atomic weapons research establishment, which I managed to soundly fluff. My parents were pretty supportive, but it probably wasn’t until I became an associate professor at RMIT that dad said, ‘Oh, okay, I guess you’ve done alright’.”

Photo by Stephen McKenzie

White lets out a rich, throaty laugh that bursts from his Montsalvat studio and triggers nearby kookaburras. He’s far more knockabout than his sensitive works might suggest: he likes a rollie, a red, a joke, and a good natter. He’s in a rock’n’roll cover band, what’s more, which plays parties and occasional pubs. But, when he throws clay onto his wheel and commits, White turns Sato-like; nothing, not even a Rolling Stones gig in Montsalvat’s Great Hall could distract him.

“The basic physics of making something means that once you’ve started, you’re locked into at least two, possibly three days,” he says in an accent that still sounds English to Aussies, but is “terribly Ocker” to English friends back home. “Something can always go wrong. I fired the kiln recently and thought it was perfect only to discover the top half was and the bottom wasn’t. A lot of people wouldn’t notice, but the difference between something being as you want it and just ok is huge to me.”

White considers himself “an evolutionary, rather than revolutionary” ceramicist, whose vessels have gotten simpler the more complex his brushwork has become. Pleas from frustrated gallery owners to “make some new shapes” fall mostly on deaf ears. “I tell them, ‘I don’t want to make new shapes, I might, but when I’m ready. There’s this constant push and pull: people who want new ideas on one hand, others who ask, what happened to your older work, we love that? Musicians recognize it. Dylan upset his fan base over the years, didn’t he, but he’s still there.” (Followed by a good chuckle)

He’s in a privileged position, of course: established and with “sufficient super” to not be swayed by trends. Still, however comfortable with his output, White gets toey before every exhibition, not least an upcoming show in May with his son Max, a painter, at Stephen McLaughlan Gallery. He sympathizes with nascent ceramicists in Australia, a country unlike Japan, not known for its appreciation of handcrafts. “Most Japanese are aware of the tea ceremony, for instance, how it’s conducted and the utensils involved. They would know the value of a tea bowl, whereas westerners would look at one and think it was carved by a five-year-old with a pen knife. For such reasons, it’s very hard to make a living out of pottery here without a day job.”

That said, at a participant level, ceramics has not only weathered doomsayer predictions, it’s thriving. “It wax and wanes. In the 1980s glass had a resurgence and was going to eclipse clay altogether, but glass is phenomenally expensive to work with. Ceramics just seems to endure. I think the pandemic might have helped its current popularity. We’re chugging along here and have almost enough for another electric kiln.”

According to White, with perseverance and patience, anyone can become a potter, but they’re largely on their own getting there. “That’s the strange thing with ceramics,” he says. “I can show you how to throw on a wheel, but I can’t ‘teach’ you how to do it, you have to ‘learn’ it. Some people take to it like that (clicks his fingers). The great ceramicists are imbued with something innate, like brilliant musicians who play with feel, beyond the academic.”

White beats the traffic from his Prahran home to Montsalvat most mornings and knows well the strangely comforting vibe locals describe when they cross Diamond Creek into Eltham. He took the Montsalvat studio in 2016, soon after retirement and the death of his wife from cancer. He needed an impetus to leave home each day. “I’d been here once or twice over the years with the kids, you know, picnics outside the Great Hall, but I’d never considered it a potential workspace until I visited an ex-student who was coordinating Clay Talk and she showed me this,” he says. “Never mind there’s no running water, I just walk down and fill my bucket… I’m lucky to have this lovely little private space in a very supportive community. Sergei, who coordinates the workshops, has become a very good friend. You feel part of a family. Yet I know that if I want to close the door and have my privacy, it’s respected.

Still, if you ever find yourself needing to knock on the door, you won’t cop a grunt from the other side.