If things go to plan, in 2053, celebrated artist Peter Wegner – of sound mind and a steady hand – will put pencil to canvas on the most symbolic work of his life: a self-portrait of himself as a centenarian. Wegner, you see, is ten years into a project for which he’s drawn more than 100 people who’ve reached the milestone. It’s an ongoing passion project, and when it’s done – probably when Wegner himself expires – a regional or state gallery will inherit the lot: hundreds of 100-plus-year-olds “frozen in time” by an artist who makes nothing from the drawings but is immeasurably richer for time spent with those he draws.

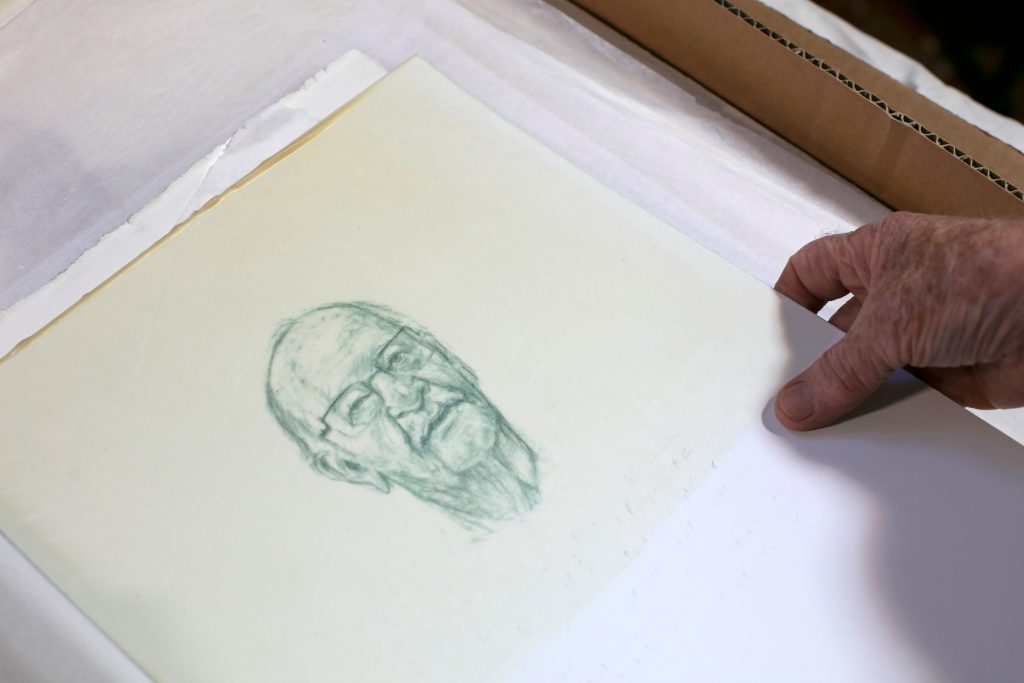

“They’re the first things I’d take in a fire,” says Wegner of the weighty folders that house his sketches, some dipped in beeswax, all dated, signed by subjects, and sprinkled with telling quotes. “I get to document two or so hours in this 100-year-old life, all the while having a conversation. Lucky I can draw and talk at the same time.”

Wegner is in his Diamond Creek studio of 25 years, where larger-than-life commissions jostle for space on scuffed Persian rugs and hardbacks on a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf. Paint spatters the floorboards and congeals in hardened mélanges on palettes dotted about. Organized chaos. It’s here that Wegner creates the commissions and portraits that fund his side project, where he painted ‘Wounded Poet’ – winner of the 2006 Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, and put finishing touches to ‘Portrait of Guy Warren at 100’, which took out the coveted Archibald in 2021. The former, one of the thousands of portraits Wegner sketched of his late friend, Graham Doyle, was celebrated for its “honesty, painterly skill, sure construction and … the compelling presence of the subject”. The latter, of beloved Sydney painter Warren, is the only centenarian portrait to make him money, $100,000 in fact. “I sketched Guy in Sydney and when I got back thought to myself, ‘I should paint him for the Archibald’. It was gut feeling. And so I flew back to do an oil portrait.”

When The Age’s art critic, Christopher Allen called Wegner’s entry a “no brainer” for the Archibald gong, Wegner thought it a kiss of death, even when his odds narrowed from 26-1 to 5-1 at the TAB. A sudden Covid lockdown only furthered his skepticism, enough that when a friend and former recipient said that winners were informed at 8am, Wegner was having toast and tea in bed with his wife, Jenny, expecting a silent phone. At 8am it rang. “It was a Sydney number,” Wegner recalls. “I answer and it goes dead. Jenny freaks out, saying, ‘that’s it, you’ve won’, and I’m like, ‘nonsense, we know lots of people in Sydney’. Anyway, it rings 20 seconds later and I hear, ‘Hello, Michael Brand, Art Galery of NSW, the trustees have decided that you’re the winner of the 2021 Archibald Prize’.”

It’s the sort of quote Wegner might add to his future self-portrait, a life-changing moment he attributes to the portrait’s “painterly features”, and a bit of symbiosis. “Guy had won the Archibald in 1967, it was the prize’s 100th year, and he, a darling of the Sydney art scene, was 100 years old. Maybe I just ticked the boxes?”

With both parents dying well shy of 100, Wegner hopes to have inherited the genes of his Aunty Rita, who made 104 and was the initial inspiration for his centenarian project. If not, he has a dozen wine bottles from a region in Sardinia, one of several so-called Blue Zones of extreme longevity, where locals partake daily. “It’s real artery scrubbing stuff,” laughs Wegner, who plans to visit all five Blue Zones (Sardinia, Okinawa, Costa Rica, Loma Linda – a Seventh Day Adventist community in California – and Greek island Icaria, with his sketch pad. Odds on he’ll be offered a tipple in most. “I’d say 80 percent of people I draw have a whiskey or sherry, or brew their own beer,” he says. “I sketched a guy in Warrnambool who has two glasses of expensive wine nightly and who offered me a glass. What am I going to say: ‘You shouldn’t drink that, it’s not good for you?’ He said, ‘I don’t care if it kills me’.”

Such moments stick in Wegner’s memory. So too the chap who hadn’t eaten lunch most of his life (an intermittent faster before it became trendy), the man who religiously walked six kilometers to mass and back each day, the fellow who found “love like he’d never known” at 97 with a woman eight years his junior, the former Rat of Tobruk who’d bought a Mini Super Cooper X at 98 (what some might call a really late-life crisis), and the man who admitted that he didn’t want to die having enjoyed his fascinating life so much.

When they do, Wegner’s “fixer”, Lachlan, a never-ending source of 100-year-olds who fit the project’s age, agility and mental requirements, adds the date to an increasingly elaborate spreadsheet. “He’s amazing,” says Wegner of his young charge. “I was in London last October when he called. ‘Peter,’ he said, ‘you should draw this woman, Elaine, 113, the oldest person in Great Britain’.” What happened next was refreshingly seamless for Wegner, who is used to several go-aheads being required before sittings. “I called her retirement home 90 minutes north, introduced myself, outlined my project and asked if we could meet. “I’ll be back in five minutes,” the nurse said. She comes back four minutes later with, “Elaine will be fine. Does this afternoon suit?” Later that day I’m sitting in a room with Elaine, who was extraordinary. What an experience!”

While Wegner’s daughters inherited their parents’ artistic sensibilities (Ari is a renowned cinematographer and Lydia a celebrated photographer), Wegner was an outlier in his own family, one of three boys born to an SES worker and housewife with no interest in or aptitude for drawing. “I want to be an artist,” he remembers telling someone at 10, and was resolute in that goal; he studied commercial graphics briefly (“get a real job” his father had told him), a degree in printmaking and a Masters at Monash, and even dabbled in emergency teaching for a while, but never put down the pencils or brush. With a bit of luck – and a bit of magic wine – he’ll be wielding both in 30 years.